Ludek Pesek's Role as Space Artist

Noel Cramer

Observatoire de Genève

(Article reproduced with permission. Adapted to the web by Arthur Woods)

Abstract

Astronomical- or "space art", is ever present in the media as well as in more technical publications related to astronomy and space exploration. That form of illustration had, and still has, a significant function in informing the public regarding the yet inaccessible new frontiers in our Solar System. We discuss here the work of Ludek Pesek, an artist who played an important role during the early missions to Mars and the outer planets. A more extensive presentation of his artwork is given in " The Art of Ludek Pesek".

Origins

Illustrative "space art" is an inescapable element of contemporary media. It is present at all levels in the popular press and is increasingly used in technical and academic publications in the fields of astronomy and space-science. It serves to depict astronomical or space exploration circumstances for which photographic documentation is otherwise unavailable. Although the connection may not at all be self evident, it is related to an ancient tradition of illustration helping to alleviate frustration in the face of adversity. In other words, we may jestingly -though reasonably - look back as far as some 30'000 years or so to cave paintings, discovered at various locations in southern France, and which are masterful "illustrations" of the local fauna encountered and hunted with some difficulty by our ancestors during the last ice age. We still do not know their full purpose, but the sophistication of their rendering is a measure of the importance they were given. They must have expressed the innermost yearnings of the small communities of hunter-gatherers of that epoch.

Artists as illustrators

However, the more customarily understood role of illustrative art is the depiction of perceived reality. Prior to the invention of photography, artists most often strove to faithfully render the world as they saw it. Apart from recording scenes and events of everyday social activity, thus bearing witness to the culture they lived in, they also played a prominent role by accompanying scientific expeditions and produced graphical documents that could not have been rendered with such economy by the written word. Often, the sense of wonder experienced by the illustrator recording a newly discovered land pervaded the interpretation of his work. Moreover, some of those illustrators were also respected as artists in the modern sense of the word as for instance Karl Bodmer, who documented the American Indian way of life around 1830. Or William Turner who is much admired today as a precursor of impressionism, but was originally trained and professed for some time as a topographic draftsman. Or even Giovanni Canaletto, whose virtually photographic portrayals of Venetian architecture in the 18th century were so accurate that they are now used by structural engineers to assess the rate of subsidence of foundations in that town.

Illustrators as artists

The advent of photography in the mid-nineteenth century profoundly transformed the recording of visual perception and tended to make life significantly more difficult for the average artist. The simplest camera instantly captures scenery with as much detail as the eye can perceive. The artist as illustrator lost much of his status, except in specific fields where his skills were still required due to aesthetic reasons or to the technical limitations of photography (for example low sensitivity of emulsions, absence of colour, etc.). Regarding the latter we may refer to the natural sciences such as for instance botany, or entomology, with their related microscopy and, notably also, astronomy. Most astronomical images of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth century were still produced by hand. In the particular case of astronomy, however, the fundamental difference with conventional exploration resided in the strict physical inaccessibility of the lands surveyed. It was impossible to mount an expedition and simply "go and see what lay in that interesting region on the Moon". Some of the more gifted astronomer-artists were not satisfied to just render what they saw through a telescope. Their specialized knowledge enabled them to imagine poorly perceived scenery on the surface of the Moon and planets with a fair degree of accuracy and then give vent to some of their frustration - as did our long forgotten ancestors - by drawing or painting them. Such competent depictions of unattainable alien landscapes anticipated adventure and exploration, the more so if the artist was able to instill a feeling of drama without unduly betraying reality.

Fig 1. Saturn's ring in the midnight sky, close to the summer solstice, viewed from a location at high latitude.

Spacecraft have yet to witness this scene predicted by Lucien Rudaux (From "Sur Les Autres Mondes", Lucien Rudaux, Larousse, 1937).

Those "extrapolated visions" were not rare in literature popularising science as well as in the daily press, and certainly did much more than is commonly recognized to arouse the interest of the general public in favour of astronomy - a science that then as now almost exclusively depends on public support. They aroused a sense of wonder and a feeling of expectancy, an urge to see at first hand those marvellous lands lying beyond the restricted frontiers of our home world. The best known of those early "astronomical artists" at the beginning of the twentieth century was the French astronomer Lucien Rudaux (1874-1947). His first lunar landscapes were published in 1910, and his major achievement as astronomical artist and popularizer of astronomy is his book "Sur Les Autres Mondes" (On the Other Worlds) published in 1937 and unfortunately out of print since then. Many of his dramatic extrapolations of landscapes on solar system bodies have since proved to be accurate, and his memory is now honoured by a Martian crater (52 km wide, named in 1973) and the asteroid 3574 (discovered 1982). However, his highest merit may be to have aroused the imaginations of countless young people, some of whom chose to consider astronomy as a career. He also inspired a new generation of unconventional but gifted artists who were later to keep on acting, unwittingly or not, as ambassadors for the exploration of space.

Fig 2. Ludek Pesek as a young man (Courtesy B. Pesek)

The space artists

There is no doubt that the space art of the first part of the 20th century, together with the rapid increase of scientifically plausible, or "hard", science fiction literature, played an important role in preparing the public to accept - and financially support - the exploration of space. Among those early space artists, two stand out distinctly:

The first of these is the American Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986), amateur astronomer, architect and visionary draughtsman who discovered Rudaux's work during a stay in England in the early nineteen twenties. He may be considered as the creator of contemporary space art and he widely popularized that art form from 1940 onwards. He is undoubtedly the best known and most influential of the space artists associated with the earliest steps of space exploration. He not only depicted scenery on the Moon and planets, but also very often incorporated the human aspects of exploration with the spacecraft and equipment necessary for that purpose. In 1979, the asteroid 3129 discovered by E. F. Helin and S. J. Bus was named after him. Few of his works are still available in press, but an outstanding biographical collection has recently been published by Ron Miller and Frederick C. Durant (2001). The other, Ludek Pesek, came across a copy of "Sur Les Autres Mondes" as a young man in his native Czechoslovakia, and was also deeply impressed by that work. He eventually painted the finest and most accurate scenes of the Martian surface and notably, Saturn, in the seventies. However, the "human element" is almost absent in his space art work, but his dramatic and credible rendering of landscapes is remarkable. Although a relative late-comer on the Western scene, Pesek's involvement with astronomy and the natural sciences as an artist began when he was a child.

Ludek Pesek was born in 1919 at Kladno, and soon after that his parents moved to the mining town of Ostrava close to the Beskidy Mountains, where he was to spend the next 22 years. His boyhood was marked by the longing for lonely mountainous country and distant lands, thus laying the ground for his later interest in geology and astronomy. His potential artistic and literary talents were recognized early and encouraged by his art teacher Vojtech Martinek at grammar school. It was also on that occasion that he first had the opportunity to use an astronomical telescope. At the age of fifteen Ludek acquired a painter's easel and began to practice his hobby earnestly; seriously enough for him to contemplate art as a profession and, having completed his secondary education, to move to Prague to study at the distinguished Nechleba Academy of Fine Arts.

The thorough training he received there was of the classical naturalistic tradition that attributed much importance to meticulous execution, and proved to be decisive for his subsequent career. As a confirmed fine artist, he possessed the technical proficiency to accurately render on canvas in a variety of styles any project that came to his mind.

The life of an artist was not easy in Czechoslovakia during the war, and maybe even less so during the communist regime that followed - i.e. if one refused to adhere to party guidelines. Ludek Pesek started producing space art while at Prague. His paintings of anticipated Moon landscapes and a series entitled The Planets of the Solar System (1963) were exhibited publicly and later on published internationally. He was also a good photographer and produced a successful photo-book, Lebanon (1965) that was translated into German and English. Then followed a prize-winning illustrated book Our Planet Earth (1967) - translated into several languages, including Japanese - as well as a first attempt at writing science fiction involving an expedition to the Moon.

Later novels in that genre - for instance The Earth is Near (1970), or Trap for Perseus (1976) -were subsequently translated into several languages and were well received notably in Germany, Great Britain and the USA. The Earth is Near is still regarded as one of the more realistic narratives of a first human expedition to Mars. We may also mention his illustrated introduction to geology and palaeontology for young people Nur ein Stein ("Just a Stone", 1972) which is a work of great originality. It demonstrates Pesek's considerable knowledge of geology, and explains how that enabled him to make imaginary landscapes "look" so credible. While still living in Czechoslovakia, however, His refusal to join the Communist Party was a permanent cause of frustration. Although he was on one occasion awarded first prize for two of his works by the Czech Artist's Association, he never gained admittance to that Union. The two works submitted were not returned and have since disappeared. Officially ignored in his country, he was even subject to police surveillance for some time.

Ludek Pesek was on holiday in Switzerland with his wife Beatrice during the Prague Spring of 1968, taking advantage of the brief opening of the "Iron Curtain", when the Soviet army invaded Czechoslovakia. They then chose not to return, forsaking all they had at home, and decided to restart a new life in the West. In spite of the sometimes financially desperate period that followed, it proved in the end to be the best possible decision they could have taken. The Peseks eventually acquired Swiss citizenship, and Ludek's former reputation as an astronomical illustrator of considerable talent soon gained him appointment to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and to the National Geographic Magazine as illustrator in the context of the discoveries being made by NASA's spacecraft during the late sixties and the seventies. Space exploration was at its heyday during that decade. The first manned Moon Landing had been accomplished on July 21, 1969. Less than a month later Mariners 6 and 7 flew by Mars and sent back 201 images that showed the planet to be less "moonlike" than the 21 low-resolution images taken by Mariner 4, in 1965, had first led to suppose; the Mariner 9 Mars Orbiter reached Mars in 1971 and began the first high resolution photographic survey of the planet providing evidence for a geologically very active past; Mariner 10 accomplished its flyby mission to Venus and Mercury in 1973 -1975; the two Viking Orbiter-Lander spacecraft reached Mars successfully in 1976 and the two Voyager missions to the outer planets were launched in 1977.

Mars, and other worlds

At that time, and prior to the arrival of the spacecraft at their destinations, very little was known regarding the conditions that prevailed locally on the Martian surface or in Jupiter's or Saturn's vicinities. The editors of the National Geographic Magazine had, however, planned some extensive coverage in anticipation of the results of the forthcoming planetary missions (see the August 1970 and February 1973 issues of the Magazine). Illustration was to be given highest priority in conformity with the traditions of that magazine, and the artist entrusted with the task needed to predict as truly as possible the environments that the spacecraft would reveal on arrival.

This sometimes led to lively confrontations between Ludek Pesek, who was the main illustrator of the series, and the mission team scientists. Early polarimetry had predicted a predominantly smooth and dusty Martian surface (we now know that it is true for extended regions on the planet). But Pesek, who had given much thought to the kinds of landscapes one would encounter in the solar system and possessed a strong intuitive sense of geology, could not conceive of such vast heavily impacted and windswept expanses being free of rocks. The two Viking Landers later proved him to be right. The landscapes surrounding each of them were remarkably similar to those anticipated by Pesek -though they tended to be even rockier - and we have had to wait for the landing of the rover "Opportunity" in 2004 to see the first truly smooth terrain on Mars. The only surprise at that time was the dun coloured sky. It was not then realized that significant amounts of fine dust could remain suspended in the thin Martian atmosphere and diffuse sunlight in its lower layers with a colour similar to that of the soil.

Fig 3. Martian dust storm (Courtesy Smithsonian Institution)

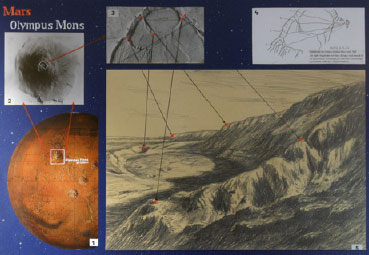

Fig 4. Constructing a Martian landscape (Courtesy A. Frei)

Another issue of disagreement, also related to polarimetry, was the fine structure of Saturn's rings. The astronomer Gerard Kuiper had reasons to believe that the particles composing them would be consistently of a few decimetres in size, rather elongated in shape and tend to be aligned perpendicularly to their orbital plane. Pesek was reluctant to accept such "unnatural" and ordered circumstances on such a large scale and preferred the other view of loosely distributed and randomly sized chunks of ice. The argument was finally put to rest by the editors of the magazine by illustrating both alternatives (see p. 182 of the National Geographic Magazine, August 1970), whereby Ludek Pesek clearly states his preference - and vindicates his vision - by rendering the second painting in a far more dramatic manner. The detailed small-scale makeup of Saturn's rings is still subject to discussion pending the arrival of the Cassini probe in 2004 and its study of the Saturnian system, but we do know that those formations are most probably composed of ice particles distributed in size from about 1 centimetre to some 5 meters following roughly a power law.

Fig 5. In Saturn's rings (Courtesy Geneva Observatory)

Fig 6. A target for future spacecraft. Pluto seen from its moon Charon (Courtesy B. Pesek)

Ludek Pesek's most famous astronomical works are undoubtedly his views of Saturn seen from within the rings (See also Sky & Telescope, January 2003, p. 110), and also his later paintings of Mars done after the results of the Mariner 9 and Viking Orbiters became available. The sharp images of the Martian topography transmitted by those spacecraft allowed him to anticipate in a quasi photographic manner the landscapes as they would appear at various locations on the surface. As he used to say, he "spent several months dwelling on Mars" painting more than 40 views of particularly interesting locations - rocky, stark and dramatically beautiful visions that the future Orbiters and Landers would prove to be so surprisingly accurate. The originals of his first Martian works are to be found mainly at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, in some private collections and as 21 works of his later Martian series donated by him shortly before his death to the Smithsonian Institution and presently in their custody.

These are, in our opinion, the very best works of art devoted to Mars achieved at that time. Much space art of very high quality has since been devoted to Mars, but one has to set oneself within the historical context to fully appreciate the importance of Pesek's work. An artist educated following the late 19th century naturalistic traditions applied his talents to the "new frontiers" of the 20th century. A truly unique series of circumstances. No artwork of such realistic quality had yet been published and distributed so widely, and the public impact of those paintings was tremendous.

Woods and fantasy

During his stay in the USA he also painted a series of some 50 deep-forest scenes such as he experienced them in the woods of the American West Coast. Those were executed in the true quasi photographic naturalistic style of his formal education and are reminiscent of the great Alpine landscapes painted by 19th century artists such as Alexandre Calame. Back in Europe and settled in Switzerland, he continued his activity as a space artist by illustrating several popular books on space exploration in collaboration with Peter Ryan and Bruno Stanek, and by producing artwork for specialized institutions such as planetariums. In 1984, the asteroid 6584 measuring some 5 km was named "Ludekpesek" by its discoverer E. Bowell.

Though a number of his paintings were commissioned by private collectors, most of Ludek Pesek's work in his later years was accomplished for his personal satisfaction. Apart from a few experiments with impressionistic landscape painting, he devoted most of his time to the creation of poetic-surrealistic visions executed in the meticulous manner he mastered so well. Those compositions are almost always presented in an astronomical, cosmic, setting. Sometimes ironic but always highly symbolic, they usually portray conflicting aspects of reality - such as a bird's nest among craters on the barren surface of the Moon, containing mottled blue eggs that emulate the image of our living Earth seen in the background, and at the same time warning us of our vulnerability with a rock that has rolled down the slope and just stopped short. Or else the breach in a decaying wooden gate held fast by an ornate lock, and where moths that were presumably imprisoned until then are gathering to set flight into the vast star field thus revealed.

Fig 7. West Coast woodland in winter (Courtesy B. Pesek)

Fig 8. The nest (Courtesy B. Pesek)

Fig 9. The moths (Courtesy B. Pesek)

Recollections

As a man, Ludek Pesek gave one at first an impression of self-effacement and modesty. But those who got to know him better appreciated his sense of humour, and were aware of being in the presence of a man of great humanity and intelligence. To capture some of his personality, we may quote him on two occasions: The first relates to an academy exercise for Vratislav Nechleba: "I presented a canvas of about one meter with the figure of a naked man, who is in a cramped pose wrestling with some sort of primeval matter (actually it wasn't as bad as it sounds). The professor stopped on his round. Bring me a chair, he said coldly. He sat down in front of the painting and kept silent for a long time. Then he uttered a memorable sentence: "Well, this is so ugly that it's beautiful". When I sold that painting to a butcher later, he pleased me with another memorable utterance: "You know what? Making good sausages is actually an art too.""

Fig. 10. Ludek Pesek in 1995 (Photo by Noel Cramer)

The second is taken from one of the last letters he wrote: "The best thing I've done in my life is that I didn't do anyone any harm." Ludek Pesek passed away on December 4, 1999, just as the World was still waiting for news from the Mars Polar Lander. He was certainly once again "living on Mars" at that moment and was barely spared the disappointment of the failed mission. His work is finally gaining recognition in his homeland thanks to the efforts of documentation made by his widow Beatrice and by relatives in Czechoslovakia. Many paintings have been sent to Prague and are presently exposed there at prestigious locations (see Miroslava Hlavackova, 2003). His manner of work was to the last as meticulous as are his paintings. The first visit of his workshop came always as something of a surprise. One entered a comfortable living room adorned with some of his finest works. Not a trace of paint could be seen on the wall-to-wall carpet covering the floor. At the best exposed window stood his almost spotless easel. Answering the inevitable question, he used to explain that his master at the Academy in Prague lectured his students that an artist who "made a mess of his workplace also made a mess of his painting....", And that was certainly not true for Ludek!

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank Beatrice Pesek for her comments and the permission to reproduce her late husband's artwork presented in these pages and in the accompanying CD-ROM. Fig 3 is currently at the Smithsonian Institution as part of the artist's donation of 21 works mentioned above. Fig 4, an assemblage by Pesek illustrating the creation of an Olympus Mons landscape, was provided by Alexandra Frei.

Bibliography

-

David A. Hardy, 1989, Visions of Space, Paper Tiger, A Dragon's World Imprint, ISBN 1-85028- 098-3

-

Miroslava Hlavackova, 2003, Ludek Pesek; obrazy, kresby, grafika, Galerie Moderniho Umeni, Roudnice Nad Labem, ISBN 80-85053- 45-4

-

Ludek Pesek, Die Erde ist nah (The Earth is near),1970, Georg Bitter Verlag, Recklinghausen, ISBN 3-7903-0000-4

-

Ludek Pesek, Nur ein Stein (Just a Stone), 1972, Beltz Verlag, Weinheim und Basel, ISBN 3- 40780215-3

-

Ludek Pesek, Trap for Perseus, 1980, (Translated from Falle fur Perseus, 1976,1, Bradbury Press, New York, ISBN 0-87888-160-3

-

Ron Miller and Frederick C. Durant, 2001, The Art of Chesley Bonestell, Paper Tiger, An imprint of Collins & Brown Ltd., ISBN 1-85585-884-3 (hb) 1 -85585-905 X (pb)

-

Lucien Rudaux, 1937, Sur Les Autres Mondes, Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie

Noel Cramer

Appendix:

See "The Art of Ludek Pesek". The artist's various styles are presented by means of 126 of his works, including some brief comments by the author which put the artwork into context.